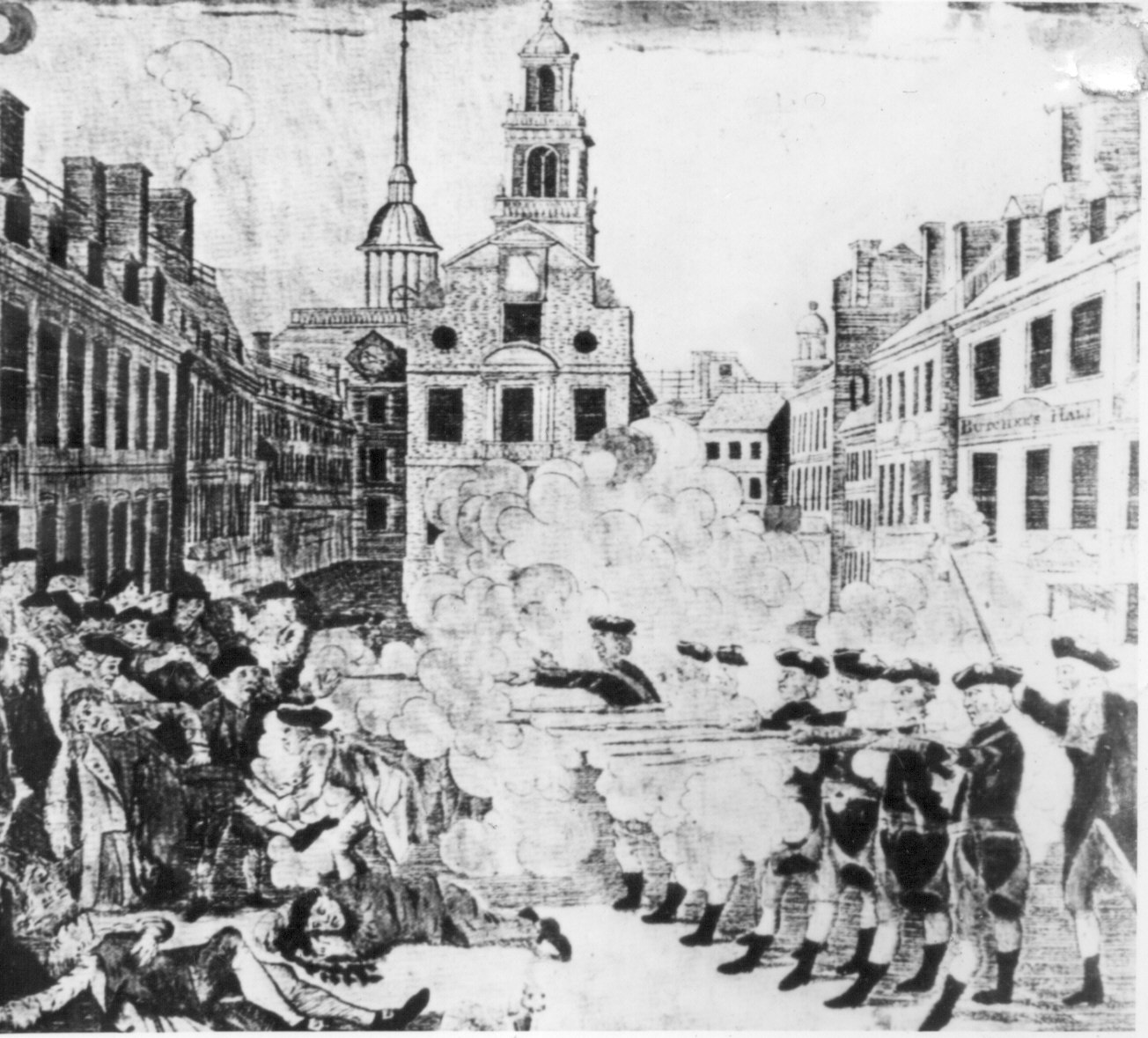

As things usually go when I’m staying in hotels, I had some difficulty sleeping last night, so I took to reading more about the Boston Massacre, and was struck by the level of similarity to the recent Trayvon Martin shooting. Both events involved mistakes on the part of both participants, both were seized upon by propagandists who fanned the anger of the mob, and both resulted in politically motivated charges of murder. No lawyer in the Town of Boston wanted to take up the case of the British soldiers who fired on the crowd, until it fell upon a 34 year old Boston lawyer named John Adams, who agreed to take the case. Adams had designs on political office, and realized taking this case ultimately would be this ruin of those ambitions, but felt it was important that the British soldiers receive a fair trial, and that the law should prevail, rather than the mob.

There was actually two separate trials, one of the commanding officer, and other of the remaining enlisted soldiers. This complicated things for Adams, because the easiest defense would be that the commanding officer had never given the order to fire, and for the soldiers that they had only been following orders. Captain Thomas Preston, the commanding officer, was acquitted, having claimed successfully that he never gave the order to fire. No transcript survives from Preston’s trial, but one did survive from the trial of the remaining soldiers, which was complicated by defense Preston had successfully made. Concluding with an eloquent closing argument, Adams managed to get all but two of the soldiers acquitted, with the remaining two convicted of manslaughter, rather than murder. In the sentencing, the two soldiers successfully appealed to the benefit of clergy, and were sentenced to having their thumbs branded.

One striking thing reading the archive of the trial is how little the practice of law has changed. I was unfamiliar with the term “benefit of clergy,” which has a rather fascinating history. Today we would call this as probation. The branding was to ensure you could not take advantage of it again in a future court, given there were no computerized criminal records in those days. In those days most felonies were capital offenses, but the legal system usually tried to figure out ways to get around having to hang every person who committed felonies. In the English legal system, one available alternative to the gallows was to waive the death sentence is exchange for enlistment in the military. Another was to sentence the convicted individual to “transportation,” to America, and later Australia, upon pain of death if one attempted to return. A third was “Benefit of Clergy,” which was based on the principle that the church was entitled to regulate its own affairs. In the early days, when literacy was generally limited to the clergy, courts would demand the reading of a biblical passage, to ensure the individual was entitled to being turned over to the church for punishment. Usually Psalm 51, which became known as the “neck verse,” for it’s ability to save one’s neck. With the expansion of literacy, this defense became more widely available, and eventually became generally available without the need to read from the bible.

This concept fell off favor with 19th century legal reforms that introduced the concept of the modern prison or penitentiary. But it was surprising to find an 18th century version of what is essentially the modern concept of probation.

There is one significant change in legal practice: Today, it would be considered a conflict of interest, and probably legal malpractice, for one attorney to represent both the commanding officer and the soldiers. This is for precisely the reason it caused a problem for Adams – it eliminates the attorney’s ability to present a possible defense on the client’s behalf because doing so would work directly against the best interests of the other client.

It’s also refreshing to note that it didn’t ruin Adam’s political career, contrary to his fears.

Oddly enough, I knew about “benefit of clergy” from some works set in the 17th century, and bothered to look it up to find out it was as meticulously researched as most of the rest of the work.

Let me guess: Neal Stephenson’s The Baroque Cycle? That’s where I knew about it from.

Yep. Just slogged through it again a few months back.

Benefit of clergy persists in Kentucky well into the 19th century. See this 1834 digest of Kentucky laws. http://books.google.com/books?id=00dMAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA1475&dq=%22benefit+of+clergy%22+Kentucky&hl=en&sa=X&ei=rb2ZT_qLA-bXiQL_ktAS&ved=0CDIQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=%22benefit%20of%20clergy%22%20Kentucky&f=false

English law had either 168 or 169 capital crimes when the American Revolution happened, including many actions that are required to be electable to public office in some jurisdictions today. A consistent application of the death penalty would have resulted in enormous loss of life.

The HBO series John Adams has an entertaining, although not completely accurate portrayal of the events leading up to the trial in the first part.

Concerning transportation to America: many Americans weren’t thrilled about having criminals sent here. The argument for transportation was that in a different climate, a different social environment, these criminals might mend their ways. See Ben Franklin’s proposal to replace the death sentence for rattlesnakes with transportation to St. James Park in London, where perhaps they would mend their ways, too.

http://books.google.com/books?id=NL5bcRP5aRAC&pg=PA229&dq=rattlesnakes+%22Benjamin+Franklin%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=u76ZT_DAC6SSiQLR-p2UBA&ved=0CEoQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=rattlesnakes%20%22Benjamin%20Franklin%22&f=false

I first learned about “Benefit of Clergy” when I slogged through “Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England”. The funny thing is, he mentions all the laws that have the Benefit of Clergy without explaining what it was, until much further into the volume…but when he does explain it, he does a thorough job, up to and including how as literacy became more universal, it became more standard.

Oh, and I just read that excerpt from Ben Franklin, as linked by Clayton: Those elongated S’s still almost read like f’s to me! (The Blackstone commentaries were facsimilies of the first edition; thus, I sort-of almost got used to reading S’s in that way.)